“ý–‘ ”∆Ķ Students Search for Solution to Drug Delivery in Outer Space

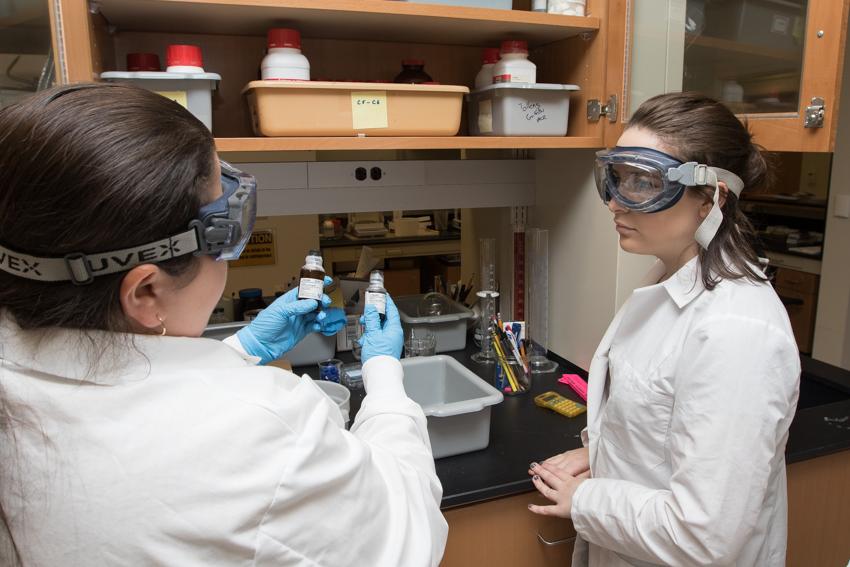

Christina Tallone, a sophomore Physician Assistant Studies major, and Daniel Schneider, a freshman Pre-Medicine major, are working with faculty mentor Pamela Cohn, assistant professor of Chemistry, to research the drug carriers that encapsulate controlled release medications.

Galloway, N.J.‚ÄĒ Drug delivery vehicles for controlled release anti-cancer drugs and insulin cannot self-assemble with uniform shape on Earth, but there‚Äôs a chance they can in outer space.

An experiment designed by a “ý–‘ ”∆Ķ team will launch to the International Space Station (ISS) this summer to get an answer.

Christina Tallone, a sophomore Physician Assistant Studies major, and Daniel Schneider, a freshman Pre-Medicine major, are working with faculty mentor Pamela Cohn, assistant professor of Chemistry, to research the drug carriers that encapsulate controlled release medications.

The obstacle preventing the successful self-assembly of controlled release drugs on Earth is shape. The carriers that enclose medication must be the same size and shape to safely release a drug to a patient. The team’s theory is that the absence of gravity will affect the structural consistency of drug carriers during self-assembly.

Non-uniform carriers result in intensified side-effects and dosage spikes, making medications unpredictable. Uniform drug carriers allow medication to be slowly released over time and eliminate the need for multiple quick-release doses, but at this time, they cannot be self-assembled uniformly when gravity is present.

The experiment was designed for Mission 12 of the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program (SSEP) through the National Center for Earth and Space Science Education. This program takes experiments designed by students (grades 5 -16) to the ISS for experimentation in a microgravity environment.

The entire experiment must be contained within a small fluid mixing enclosure, since space is tight aboard the ISS. Indigo dye will be used to simulate a drug and will mix with a combination of molecules that self-assemble into a drug carrier.

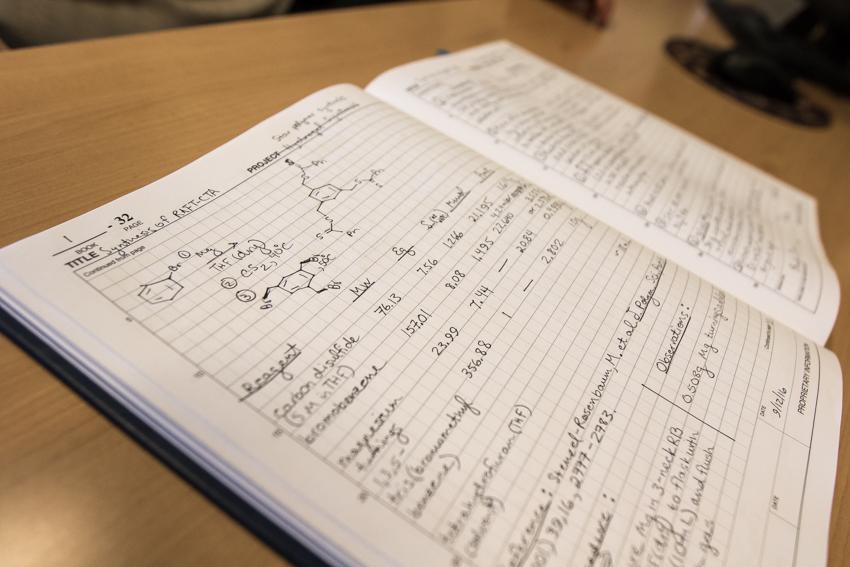

The team will use “ý–‘ ”∆Ķ‚Äôs Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectrometer to record the structural identification and weights of the molecules they‚Äôll be sending to space.

In space, the components in the enclosure will be undisturbed by gravitational forces, so they will be influenced only by their own intermolecular forces such as surface tension.

When the experiment returns from space, it will be analyzed and compared to a control experiment. Digital imagery from an atomic force microscope will be processed to determine shape and size consistency. Other analytical techniques will look at weight in relation to temperature and the release of dye in relation to time under ultrasonic conditions.

If the team discovers that structurally consistent drug carriers can be created in a microgravity environment, then controlled release drugs can be made in laboratories that simulate weightlessness on Earth. If not, then there are likely forces unknown to science that impact self-assembly.

Christina Tallone, of Hamilton, N.J., knew early on that she wanted to pursue science. At age 5, she got a children‚Äôs stethoscope from Toys ‚ÄėR Us, which eventually led to flash cards that helped her learn about the human body. She attended the Health Science Academy, a technical high school in Mercer County, and was learning how to administer shots and how to check vital signs at the same time as her older sister who was in nursing school. Her goal is to become a dermatology surgeon.

Daniel Schneider, of Tabernacle, N.J., is only a freshman, but he‚Äôs known since he was young that he wants to become a doctor because he loves helping others. He entered “ý–‘ ”∆Ķ with Chemistry I and IV already completed as well as fire and EMT certifications. At age 14, he was an explorer at the Hampton Lakes Volunteer Fire Company, an experience he describes as difficult, but really cool.

Tallone and Schneider’s longtime passion to make a difference in the field of medicine coupled with guidance from Pamela Cohn, who earned an organic chemistry PhD and studied polymer science as a postdoctoral researcher, make a dynamic force. Not even gravity can stop their experiment from taking drug delivery science to the next level.

About the Project:

The Mission 12 project at “ý–‘ ”∆Ķ is a partnership between the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, the “ý–‘ ”∆Ķ Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Collaborative, the School of General Studies and the School of Education.

The Student Spaceflight Experiments Program [or SSEP] is a program of the National

Center for Earth and Space Science Education (NCESSE) in the U.S. and the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education internationally. It is enabled through a strategic partnership with DreamUp PBC and NanoRacks LLC, which are working with NASA under a Space Act Agreement as part of the utilization of the International Space Station as a National Laboratory.

Story reported_ by Susan Allen.

Last year's Mission 11 space experiment sent spores to space to determine if fungus is a potential force for improving agriculture in space.

Contact:

Diane D’Amico

Director of News and Media Relations

Galloway, N.J. 08205

Diane.D'Amico@stockton.edu

609-652-4593